By Steve Duin

stephen.b.duin@gmail.com; for Oregon Journalism Project

OREGON — Imagine that you recently retired in the state you love. You’ve raised a family, paid off a mortgage. Supported nonprofits and the local restaurants in your community. Against all odds, you’ve even put some money away for the grandkids.

You’ve prospered through a good life, most of it in Oregon, but your accountant has just lowered the boom: You can’t afford to die here.

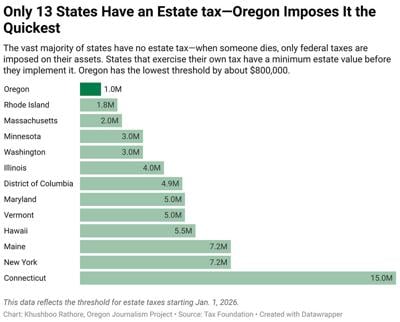

When taxpayers breathe their last in 38 other states, including true-blue California and blood-red Idaho, those state governments have no interest in claiming a share of the savings, retirement accounts, and family homes they leave behind. Of the dozen states that do, none is so greedy as Oregon.

Connecticut has an estate tax, but — mirroring the federal government — it exempts the first $15 million of an individual estate or the first $30 million for a married couple, while Oregon’s exemption is $1 million, the lowest in the land (see chart).

If your savings and home equity total, say, $1.5 million at death, Oregon will claim 10% of the amount that exceeds its exemption, or $50,000. If you’re the rare Oregonian with investments of $10 million at death, the state will pinch 16% of the amount that is not transferred to a surviving spouse. That pencils out to $1.4 million.

State economists predict Oregon will collect $422.8 million in estate taxes in fiscal year 2025. While that figure pales beside the $13 billion due in personal income taxes, our state government can’t curb its addiction to seizing a share of your nest egg.

Oregon’s $1 million exemption was set in stone in 2002. It has never been indexed for inflation. (If the amount had simply increased with inflation, it would be $1.83 million today. Meanwhile, home values, the greatest sources of most families’ wealth, have more than doubled since 2002.) That means more estates are paying the tax — the number more than doubled from 2012-2022, state figures show, and today’s total is expected to nearly triple by 2050.

Appeals to the Legislature to mitigate the damage routinely go down in flames, or vanish in committee. At the same time, Republican state Rep. Kevin Mannix of Salem and John von Schlegell, co-founder of Endeavour Capital, have separately filed 2026 ballot initiatives to abolish estate taxes. (Editor’s note: Von Schlegell is a member of the board of directors of Oregon Journalism Project.)

The Democratic majority in the Legislature is unconcerned that Oregonians in their golden years are advised to leave the state to avoid the tax, and no one is tracking the number who do. In a society where high-speed internet and home delivery of virtually everything have made it easier to live just about anywhere, Oregon is betting that people will, in effect, pay extra to die here. That’s a risky bet when other states — including all that but Oregon — offer a dramatically cheaper final chapter.

The argument for the status quo is eloquently delivered by Daniel Hauser, deputy director of the Oregon Center for Public Policy, a lefty think tank.

Noting that Oregon expects to collect more than $1.1 billion in estate taxes during the 2027–29 biennium, Hauser says, “If you asked me to find a way to raise $1 billion that would have the smallest impact on low-income and working families, I think the estate tax is where we should start.”

Quite reasonable, that. I hear voters cheering in the wings. Rather than balance the books with a sales tax — which hits low-income families the hardest — Oregon taxes the rich.

“That assumption is flawed,” says Richard Solomon, a Portland accountant and former member of the Oregon Investment Council, who shares Hauser’s concern for preserving essential state services. “The tax isn’t exclusively paid by the rich. It impacts people like police, teachers, and skilled laborers.”

And what amount of “wealth” does it take for an Oregonian to eventually feel the sting of our estate tax? For many, a mortgage-free home and a 401(k).

“Paying off your mortgage and saving for retirement is often enough to have Oregon estate tax liability,” says Steven Bell, senior vice president at Ferguson Wellman Capital Management. “I’ve seen it pencil out once or twice where the answer when considering income and estate tax estimates is: ‘It will pay for the new house.’”

Is it any wonder, then, that families are calculating the cost of retiring to Boise or Eureka, rather than hunkering down in Bend or Enterprise, in order to dodge Oregon’s estate taxes?

Financial advisers and estate planners routinely hear such anguished questions, and Bell says that one of the “best” tax-planning choices is to move out of state. When Oregonians migrate, he adds, “they rarely move in the last six months of their lives. They are spending years in that other jurisdiction, and that is income tax that is also not coming to the Oregon Department of Revenue.”

•••

This story was produced by the Oregon Journalism Project (oregonjournalismproject.org), a nonprofit investigative newsroom for the state of Oregon.

Commented