By Flora Martin Gibson

Columbia Gorge News

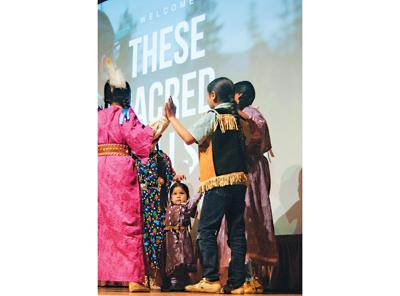

THE GORGE — A local screening of a new documentary, “These Sacred Hills,” shared the stories of Yakama Nation citizens fighting Rye Development’s plan to build a green energy storage plant on one of their sacred sites.

The project to place an underground tunnel, two ponds, and other facilities on Pushpum — about eight miles south of Goldendale — recently had its water quality certification affirmed by Washington’s Pollution Control Hearings Board, despite an appeal from Columbia Riverkeeper, Yakama Nation, and multiple nonprofits. The film project is billed as “a fight to protect sacred lands and sovereignty.”

Filmed by Jacob Bailey and Christopher Ward, together with the Rock Creek Band of the Yakama Nation, “These Sacred Hills” features gatherer, biologist and Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC) Watershed Department Manager Elaine Harvey; Jeremy Takala; Indigenous Affairs Desk Reporter B. Toastie Oaster of High Country News; and professor Andrew Fisher, among others.

Takala is a member of the Rock Creek Band of the Yakama Nation, one of 14 elected officials on the that nation’s council, and current chair of CRITFC.

“People think it’s just nothing, but ... it has its time to provide. It has its time to have medicines. It has its name. It’s very special to all of us. And when you take away those pieces, you’re taking away that livelihood for all your youth,” he said prior to the film screening.

He added, “You know, part of our fisheries program is to restore runs. A lot of our kids don’t know what bridgelip sucker are. Or mussels. Because it’s been absent in our lives for decades. And when you bring that back? They’re exposed to it. They’re going to learn it in our language. They’re going to learn how to process it, how to take care of it and honor it. That’s why it’s important. That’s why it’s important to preserve and protect these areas so that they have the ability to go out and gather.”

Working around their jobs, the team created this film in their free time, speakers said. It’s a grassroots work of their own time and money. Filming was supposed to last a single day. Several elders and children and others took the two film-makers on a food gathering trip to the area Rye Development wants to develop, and they decided to tell the whole story.

That took three years. The two videographers participated in food gathering and hunting. Filming sacred songs and dances is not permitted, but the band has decided to share some other parts of their story, hoping to raise awareness about what they are fighting for.

“Our elders, they felt impacts of railroads, highways ... it’s continuously coming and impacting our tribal people, you know, in so many different ways. It’s impacting us. It’s really hurtful. It’s really hurtful because we’re losing our lands, where we’re supposed to be able to gather our food,” Harvey said.

Shrub steppe is “real important to us, to wildlife, to fish in their migratory corridors ... habitat for birds. And we’re feeling these impacts. We can’t go to these places anymore.”

Those “places” stretch from beyond Wenatchee to Ellensberg and south to Oregon, Harvey noted. “We make our seasonal rounds, and we’re seeing the changes and the impacts in industries having urbanization, parcelization ... It’s really hurtful, because we’re concerned about our future generations, and that’s what it’s all about. We want our children to be able to fish. We want our children to go out, be able to go seek those roots, gather the moss, pick the berries, and today, I can honestly say, working in the Department of Natural Resources and Fisheries and at CRITFC, each one of our foods are under attack.”

It’s an issue that stretches far beyond the Mid-Columbia region, the speakers said.

Takala told the story of a visitor from the Mekong River. The visitor was a Native advocate for traditional fishing grounds on the Mekong — which, unlike Celilo Falls, still exist. For now; Cambodia planned, then scrapped, two new dams in addition to those already built. A dam under construction in 2024 was expected to flood more than 500 families and impact 20 villages, according to Associated Press. Some planned dams could flood the fishing sites on the Mekong.

Though not an English speaker, the visitor found kinship with the four Treaty Tribes’ similar fight here. “I said, ‘It’s not just going to be dams next. They’re going to push green energy over there too.’ So I really feel for the Mekong people,” said Takala.

The film team hopes to screen the film as much as possible this year, in different parts of the United States. They’ve submitted to various film festivals — including one in Copenhagen, Denmark, where Rye Development’s financial backers are based.

Later, the film will be free to anyone who wishes to host a screening. For questions, visit sacredhillsfilm.com.

Commented