Is energy “green” if it costs part of Yakama Nation’s culture?

GOLDENDALE — Yakama Nation activists say the $2.5 billion Goldendale pumped storage project, which is on track to complete its permitting for construction on a former aluminum smelter site, could irrevocably destroy a sacred cultural landscape about eight miles south of Goldendale.

Yakama Nation and allies oppose the project that would destroy at least six known archaeological sites and three traditional cultural properties — including Pushpum, a sacred area where part of Elaine Harvey’s community, the Kah-Milt-Pah band of Yakama Nation, gather traditional First Foods and medicines.

“The tribes are not against renewable energy, and they’re pursuing their own renewable energy, like Yakama Nation, like Warm Springs, Nez Perce and Umatilla, they’re all pursuing renewable energy projects on their own land,” said Harvey, watershed department manager at Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission. “And you know that we promote renewable energy, but in a responsible way.” The problem is the location of this — the Northwest’s biggest pumped storage facility — atop traditional cultural properties.

Washington Department of Ecology (DOE) and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) environmental impact statements found the 681.6-acre project would cause unavoidable, irrevocable harm to archaeological sites, cultural practices and traditional gathering, but both agencies recommended the project be licensed for construction. Visual degradation of the landscape could also interrupt spiritual and cultural practices.

Yakama Nation has repeatedly stated that no mitigation or compensation for this loss of cultural heritage is possible.

Rye Development, the developer, is also pushing for the project to go ahead.

"We strongly believe the Goldendale energy storage project is key to Washington's clean energy future," said Rye Development's project manager Erik Steimle. "It'll help keep the lights on even in extreme weather events, and as we transition to carbon-free electricity."

Klickitat County Commission Chair Lori Zoller declined to comment.

The facility would help meet Washington’s green energy goals, storing energy from intermittent renewables like wind and solar. Klickitat County would get $14 million in annual tax revenue, and up to 3,000 temporary construction jobs for five years.

Klickitat County's budget for 2024 was $65 million.

A few more permits are needed before the project can break ground. Columbia Riverkeeper is currently appealing Rye’s water quality certification, alongside American Rivers, Yakama Nation and Washington Conservation Action, said Staff Attorney Simone Anter. She could not speak about any future legal proceedings.

Some 2,366 people signed Riverkeeper’s latest petition opposing the project.

Rye planned and permitted, but has not yet built, another pumped storage facility in the Klamath Basin, Oregon, opposed by the Modoc Nation.

Pumped energy storage

If constructed, the closed-loop system would consist of two ponds connected by underground tunnels, one atop the ridge at Pushpum and one 2,400 feet below beside the Columbia River, near the smelter location. A powerhouse, switchyard and utilities would also be underground.

The needed roads already exist. About $10 million from Dutch-based Copenhagen Investment Partners, the project owners, will pay for the polluted former smelter site’s ongoing cleanup.

Water would be pumped up from the lower reservoir and stored atop the hill. The upper 63-acre reservoir would act as a giant “battery,” a storehouse of potential energy. When that energy was needed, water would be released to flow back to the lower reservoir, past turbines generating electricity for the John Day Dam Substation. This type of energy storage has been used for decades, with more than 40 facilities in the U.S. by 2010, according to an analysis from Stanford University.

Economically, Steimle said the project will service utilities with transmission access, who are now required to have green energy storage. They’ll pay for a certain amount of water to be pumped up and stored in the upper reservoir. When the sun isn't shining or the windmills aren't turning, the facility drops their water back down. It could provide 1200 megawatts of energy — enough to power half a million homes — for 12 hours when the upper pond is full.

Protecting Pushpum

Pushpum is interpreted in English as the “Mother of All Roots,” while nonnative people named the ridgetop Juniper Point for the presence of that medicine, Harvey said. The seed bank safeguards important traditional foods and medicines.

A seed bank is a natural accumulation of seeds and fruits in the soil, with diverse plants waiting to sprout when conditions are right — insurance against the deaths of living plants, as long as the soil surface is not destroyed.

The Kah-Milt-Pah gather First Foods here for ceremonies. Other foods and medicines grow all the way from ridge-top to river. For generations, private landowners nearby have allowed Harvey’s people access to their land. “Many of the high-elevation areas like this are significant to our people, because that’s where we’re going to find our traditional foods, and that’s where our medicines grow, and we continuously come here every year,” Harvey said.

The site is sacred to Yakama, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation, and others. In a 2021 resolution, the Yakama Tribal Council said “the proposed pump storage development violates the Yakama Nation’s inherent sovereignty and Treaty-reserved rights through direct, permanent, and adverse destruction of nine Traditional Cultural Properties of religious and ceremonial significance, and the reduction and elimination of access to gather food and medicine roots ...”

While most of the project lies on private land owned by NSC Smelter, LLC and formerly operated by Lockheed Martin Aluminum, a portion is on federal Army Corps of Engineers land and thus is subject to tribal treaty rights. “The treaties that the U.S. government made with the tribes are supposed to be the supreme law of the land,” Harvey said. “And in those treaties, our ancestors reserved the right to fish, hunt and gather.”

A bit under 200 acres of wildlife habitat would be lost and a significant part of Pushpum itself destroyed, said Harvey and Anter. Rye has pledged to replant native vegetation, but since some operations require unvegetated areas — for example, discouraging wildlife in the ponds — not everything can be replanted. Some plants here are endemic to the Gorge, Harvey said, meaning they grow nowhere else on earth.

As for Columbia Riverkeeper, their concerns include the use of 2.49 million gallons of Columbia River water for initial fill, topped up with 117 million gallons annually; and the potential for pollution if groundwater changes its movements through the former smelter site, said Anter.

Asked by a High Country News reporter what compensation the project could offer Yakama Nation citizens, Steimle suggested jobs at the facility — an offer they rejected, according to the reporter’s coverage, Harvey and Anter.

After construction, 25-60 permanent jobs will remain, according to the project’s website. They’ll be typical hydropower operation jobs, a kind of work that already exists along the Columbia, Steimle said, meaning he expects to hire people from this region.

Harvey was skeptical of the long-term impact in jobs. “They come here, stay temporarily. They do the job, then they leave. And that’s what has happened with the wind and it’s happening with the current solar projects,” she said. “They’re not hiring people in Goldendale. And if they do, they’re getting the low-end jobs.”

Pumped storage projects have been proposed on this site twice before and struck down. Scott Tillman, CEO of Golden Northwest Aluminum Corporation and then-owner of the site, pitched the idea in 2008. First Klickitat County, then Rye Development tried to implement the plan.

Yakama Nation didn’t know until December 2017, when FERC issued a public notice of acceptance for the application, according to reporting from High Country News.

By then, said Harvey, it was too late for tribal government to have a meaningful say in where the project would be located. That’s not unusual.

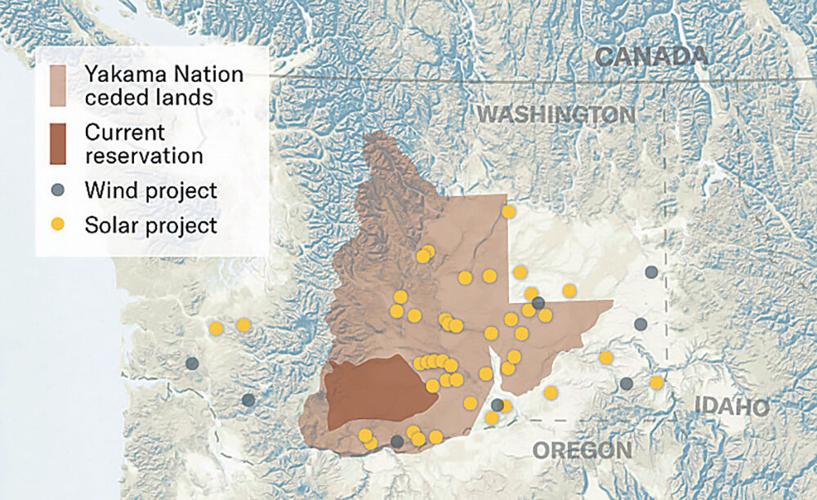

Harvey formerly worked for Yakama Nation, when 40 solar projects were proposed or under construction, an estimated 80% on Yakama’s treaty lands in central Washington. Many locations were chosen without Yakama Nation's knowledge, she said. Once money was spent, leases established and studies done on a particular site, tribes were asked for input. Harvey said earlier collaboration would be key to avoiding conflicts like this.

A map of wind and solar projects proposed or built in Washington by 2023, about 60% on Yakama Nation’s ceded lands. Eight more have been proposed in Washington since this map was made, but Washington Fish and Wildlife did not say whether they were on Yakama’s ceded lands.

Graphic courtesy High Country News, reprinted here with permissionGovernment consultation issues

In August 2021, FERC chose Rye to be its representative in government-to-government consultation with tribes. Yakama Nation refused to consult with a developer instead of the government itself.

FERC countered that appointing corporations for the role was its standard practice. If the tribe wouldn’t consult with Rye Development, FERC concluded, it could file more public comments instead.

But Yakama Nation can’t disclose sensitive cultural information to developers or to the public via public comments. Doing so exposes sites to looting and destruction and loss of cultural resources, or damage to cultural properties like petroglyphs, said Harvey. There’s a history of people “finding out these details, going out there and ruining these places,” Anter added.

And FERC won’t let Yakama Nation disclose that information in confidence. The sticking point is Rule 2201, which legally prohibits off-the-record communications. Any information Yakama Nation gives in a contested consultation must be disclosed to some officials and stakeholders, FERC said.

FERC wrote Rule 2201 for itself in 2000.

Yakama Nation refused to disclose that sensitive cultural information to developers and officials, but that means FERC won’t take it into account.

Harvey explained why that hits close to home. “Throughout the whole FERC hearing, everyone kept saying, ‘There’s no Indians here. They all live on the reservation, and they’re like 90 miles away,’” she said. Harvey’s lived almost all her life in Goldendale, and said her people continue traditions of hunting, gathering and living in the area.

Asked for comment, Steimle said, “We understand, first, the value and importance of consultation with tribal nations to address the protection of cultural and botanical resources. As well, we met with tribal leaders and also hired members of the tribes to complete a number of studies that we incorporated into our applications.”

However, these studies do not constitute good-faith government-to-government consultation on the project, which Yakama Nation maintains still has not been done. Explaining the legal requirement, Anter said, “Consultation is a way to make sure that cultural resources are not being destroyed, that the Tribe’s input is being taken into account. And part of the planning process. And in this case, we’re not seeing that happen.”

Rye claimed in its latest letter, filed with FERC this July, that the early archaeological studies, public comments and filings meant the project’s “impacts on historic properties were completely studied and well understood.” The letter offered mitigations like canine surveys to locate burials, locating and studying sacred sites and buying an equal number of acres where First Foods grow, elsewhere in the region.

"We are committed to working with Tribal Nations to ensure protection of sites that hold cultural significance to them. And we remain open to meeting with members of the Yakama Nation tribal council to discuss their concerns," Rye told Columbia Gorge News.

Steimle noted “significant and costly” modifications to the plan: Burying as much infrastructure as possible and moving the upper pond back from the ridgeline to hide it from Juniper Point. “We certainly understand that our efforts don’t take the place of nation-to-nation consultation that the Tribe can have with the federal government,” he said.

Yakama Nation has said nothing can mitigate the loss of archaeological sites and significant cultural areas. Anter confirmed six archaeological sites would be destroyed.

In the court of public opinion

In the early stages of planning, after hiring Yakama Nation technical staff to complete archaeological surveys, Rye stated that Yakama Nation didn’t oppose the project, Anter said. That “skewed” public opinion of the project, making opposition “really challenging in the early days.”

DOE conducted the state environmental assessment. At one point, Rye submitted a DOE letter which acknowledged their project proposal to FERC as a letter of support — prompting the letter’s writers to issue a clarification: They were neutral parties, not supporters.

The national Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) stated in a July 26 letter, “Throughout the early licensing process … FERC dismissed comments from the Yakama Nation regarding the presence of important properties of religious and cultural significance at the proposed project site as premature and irrelevant …” The council noted the project could “continue and extend” the damage to Tribal ways of life already inflicted by dams.

Rye responded in a letter that ACHP “appears to fundamentally misunderstand the nature of the project." The facility can’t be compared to a dam because it doesn’t directly impact river flows or fish runs, said Rye, and reiterated claims that Rye’s hiring of Yakama Nation technicians to carry out archaeological surveys, and the public FERC filings, ensured the project would incorporate their concerns.

Rye’s latest letter also said the project can offer Yakama Nation continued access to the area, as mitigation. But Steimle told Columbia Gorge News that decision is out of Rye’s hands. Only the landowner can really make that decision, he said.

In a statement through Rye, Tillman said "I have always offered access to the property and will continue to do so."

The smelter land is mostly private and zoned industrial, with a data center and other projects proposed. This is perhaps the best area for pumped storage in Washington, with the right infrastructure, abundant solar and hydropower, and a steep rise in elevation. DOE's has said it’s committed to returning the site’s “productive economic use.”

When dams were constructed, one of Harvey’s maternal grandmothers was displaced from her village site near the proposed Goldendale project. For her, this is personal. “It’s just a desecration to put a 30-foot diameter tunnel through our sacred mountain,” she said at a webinar held in solidarity with Dine and Navajo activists. “I can’t imagine ... what am I going to tell my grandkids?”

She isn’t sure if there’s a realistic chance of stopping the project, but said she’s going to keep fighting. “I want to tell my grandkids: ‘Hey, I didn’t just sit on the side and let this happen.’"

Pressuring tribal lands

“Out elders told us what happened when the dams were built and now we’re feeling that same pressure on us and our resources,” Yakama activist Harvey told a webinar held in solidarity with Dine and Navajo activists, who are fighting another pumped storage project on their own traditional cultural landscape at Black Mesa.

Across the U.S., the worsening climate crisis is inspiring a green energy transition. That’s also inspiring a wave of rapidly-designed green energy projects that disproportionately burden Tribal nations on whose land many are being built, impacting sacred sites and cultural resources, Anter explained in an interview later.

“We’re also seeing a greenwashing of otherwise harmful developments and minimization of the destruction of tribal cultural resources,” she’d told webinar attendees.

By 2023, 51 wind and solar projects had been proposed in Washington, with at least 34 on Yakama Nation’s ceded lands, their 10-million-acre treaty territory in central Washington. That’s at least 60%. Since then, eight more projects have been proposed in the state, said Michael Ritter of Washington Fish and Wildlife.

Solar energy can be especially destructive of shrub steppe habitat, which covers eastern Oregon and Washington and is vital for many hawks, antelope, deer, elk and birds. Statewide, significant areas of such habitat have been lost. Solar energy can require sections of vegetation razed and fenced in.

Anter said it’s important that proposals like this are not fast-tracked by regulators despite cultural resource issues and a lack of consultation. By eroding trust between tribal nations, governments and NGOs, conflict can make green energy projects that legitimately don’t impact tribes that much harder to build.

To Harvey, that’s continuing a long tradition of not-quite-green energy. “Look back into the past and see what the Columbia River tribes have lost because of renewable energies, such as the hydro systems on the main stem Columbia,” she said in an interview. “We’ve lost Celilo Falls. We’ve lost burial sites, village sites, our people have been left homeless. And as a result, you look at the high rates of alcoholism and homelessness amongst the Native American communities on the Columbia Gorge. … And I think people need to look at what the tribes have already lost, and try to look through our perspective — what are we trying to protect?”

Commented