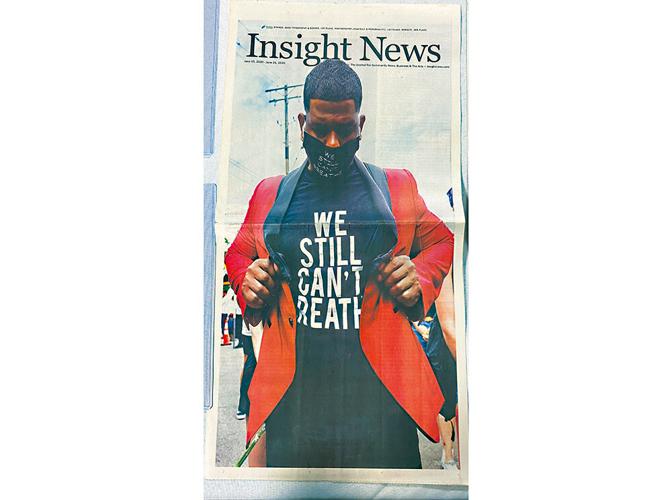

THE DALLES — About 40 people who attended a mobile museum and lecture on Black history, got to touch and examine more than 150 museum-quality items dating from the transatlantic slave trade, through hip-hop culture and the Black Lives Matter movement, and heard from the museum’s founder, Dr. Khalid El-Hakim.

The visit by the Black History 101 Mobile Museum was organized by EQuity Through United Action League (EQUAL), Columbia Gorge Community College’s (CGCC) student-led social justice club, and the CGCC Foundation. Librarian Tori Stanek opened the library to a one-day exhibit on Jan. 13.

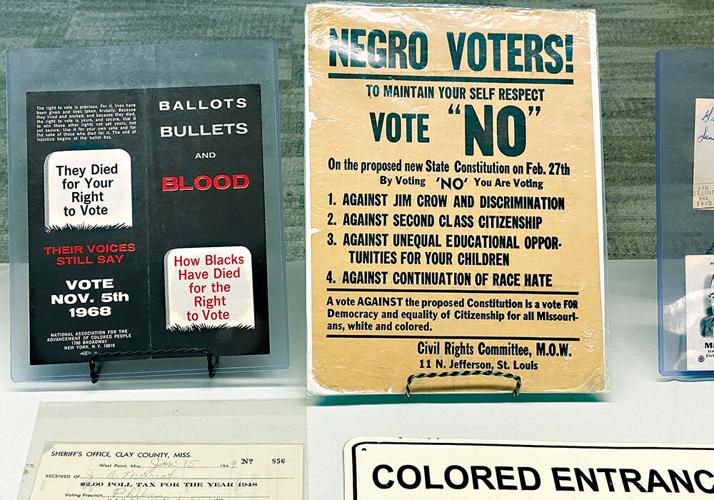

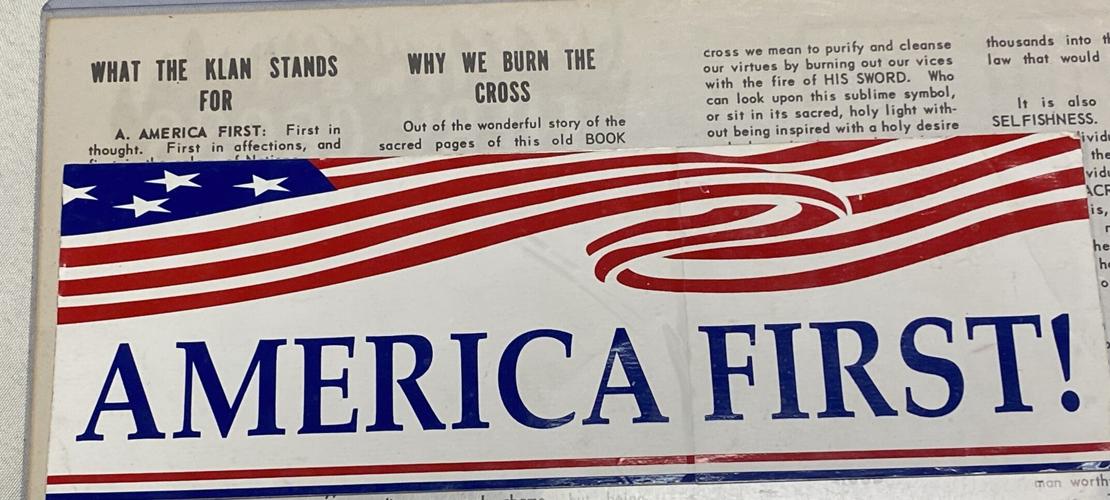

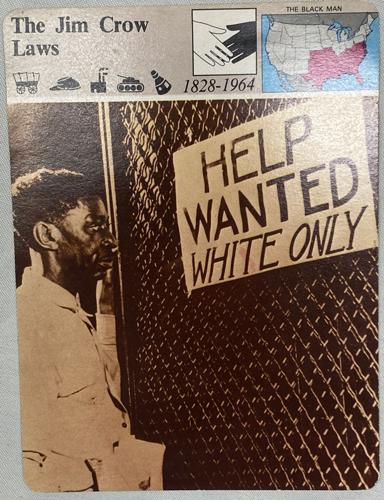

Circulating guests started with the slave trade, confronted with a set of shackles, Ku Klux Klan items, and beads and art from enslaved peoples. By the other end, they’ve reached modern bumper stickers that echo the slogans of much earlier Klan papers, and Black Lives Matter pins.

El-Hakim is an educator and activist who founded the museum 30 years ago, as a student at Ferris State University. There, El-Hakim was inspired by the Jim Crow Museum of racist memorabilia, founded by sociologist Dr. David Pilgrim.

Every week, Pilgrim would bring a Jim Crow-related artifact to sociology class, so students could have conversations on the origins of racism in America. “These were objects that I had never seen before, my classmates had never seen before, just like some of you who are walking through this exhibit today,” said El-Hakim in his lecture. “... We’ve heard about racism in America. We’ve seen, maybe photographs or segregation signs, and we are probably familiar with some of the stereotypical images, but to see these things live and in person is a whole different type of experience.”

El-Hakim’s team takes the museum (Klan robes, shackles, Grateful Dead albums, photos of violence and all) to institutions and events around the U.S. to host those conversations. He began this lecture with a trip he and a classmate took from Michigan to Tennessee — his first visit to the South, at age 21. “We walk into this gas station, and we see Confederate flags all over this gas station,” he recalled. El-Hakim “liberated” a racist figurine — not an antique, a mass-produced modern statuette, an ugly caricature of a Black person — and it became one of his museum’s first items.

“... A lot of this material is very heavy, heavy material, and I want us to be able to have a real critical conversation about the material,” El-Hakim said. For this purpose, he introduced “four truths” used to understand the discussion.

One: the social truth. “That dominant narrative that we all have gotten about history, all right? And it’s very much whitewashed, but it’s what we get through textbooks, the media, through museums.”

Two: personal truth, “that comes through your own lived experience.” This is an individual’s own understanding and personal experience of the issue, El-Hakim explained.

Three: Forensic truth. “That’s the actual facts about an individual artifact, the size, the color, the utility of it and the type of material ...”

Four: A healing truth. “That’s the narrative that addresses that injustice and really empowers the victim of it, and really creates a space for us to have these conversations and for that healing to take place.”

Then he presented a T-shirt which showed a Black person in the sights of a rifle, which was on sale in 1991.

El-Hakim explained that artifact was part of the racist response to contemporary events, including police brutality. Rodney King had been beaten by police in Los Angeles (two out of four officers would later be sentenced to prison terms), and a citizen caught the encounter on film, sparking national coverage and outrage. El-Hakim, who was learning about Black history through hip-hop at the time, recalled NWA’s song “Police” racing through Black communities at the time. And there was something else going on: Martin Luther King Day.

Four days after King’s assassination, in 1968, Congressman John Conyers introduced a bill to create the holiday. It wasn’t until 1983 that Ronald Reagan signed it into law. Southern states reacted to their new mandatory holiday by instituting “Robert E. Lee Day,” celebrating the Civil War Confederate general alongside the nonviolent activist. And Arizona, the last state to begin celebrating Martin Luther King Day, did so only after Public Enemy, through a protest song, threatened a boycott of Arizona.

One of Public Enemy’s founding members, Professor Griffin, attended the lecture in The Dalles.

The artifacts El-Hakim showed include racist memorabilia reflecting various reactions to this progress.

“We all know that people are not born racist, right? We all know that, but people are socialized into this type of behavior,” El-Hakim said. He went on to explain the books, images, and artifacts that contributed to that socialization, and the idea that “Blacks were genetically inferior to whites.” Children’s games, which included Black children as weapons’ targets; “Little Rascals” episodes showing violence against women and people of color; and in 2012, gun targets of Trayvon Martin — another victim of police violence who was Black.

“I don’t mean to be political, but everything’s political,” El-Hakim said. “...This bumper sticker is new. All right, this coin is from the 1920s. This Klan brochure is from the 1950s. What the Klan stands for? ‘Number one, America First’” — a slogan that still appears on “patriotic” paraphernalia like bumper stickers. “This is nothing new,” he said.

El-Hakim also talked about discrimination in the military, as Black soldiers fought for the U.S. starting in the Civil War — including the Harlem Hellfighters, who fought in the front-line trenches for 191 consecutive days in World War I, something no other group of American soldiers did. Another fact, long covered up, until someone found the records: the Tusgegee Airmen won the first Top Gun award. Black soldiers also performed jazz abroad, introducing this quintessentially Black art form to Europe during the war.

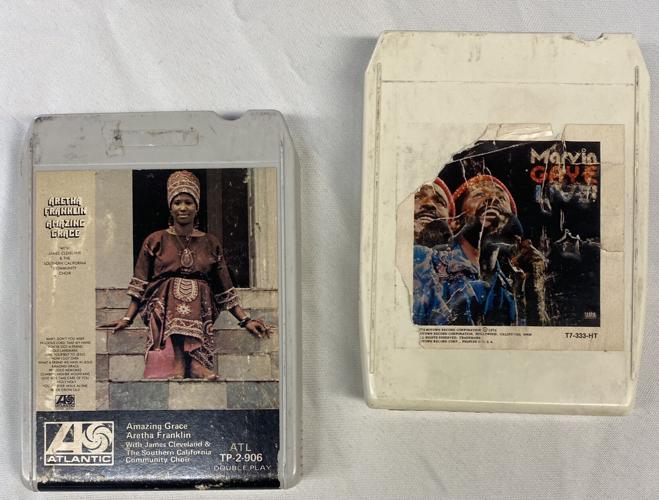

The Black Panthers weren’t just the white version of the KKK, El-Hakim paused to say. Bob Dylan wrote songs about the Black Panthers, who listened to his music while putting the Panther newspaper together. The Grateful Dead fundraised for them. Contrasted with photos of white supremacists holding swastikas in America less than two decades after World War II.

El-Hakim then fast-forwarded to 1995, when a call came out for “1 million black men to go to Washington, D.C., under the themes of atonement, reconciliation, and responsibility.” El-Hakim was one of the more than 1 million who showed up that day, collecting posters, bumper stickers and even his subway card. Speakers that day included Dr. Maya Angelou, Dr. Betty Shabazz, Dr. Dorothy Heights and Rosa Parks.

Despite the photographs of the packed capitol streets, the National Parks Service disputed the numbers.

“People often ask ... ‘Why are you bringing up this old stuff? Why do we have to go down this road over and over again?’ And you know, in 2025, it’s becoming more apparent every day why this is necessary.”

In proof, he showed a racist advertisement — a distorted cartoon of a black child — from 1922; El-Hakim noticed this tattooed on a man’s arm in a Portland coffee shop not long ago. And a man he encountered on a beach in Michigan, while playing with his 3-year-old daughter, who openly showed swastika tattoos, and the lightning bolt tattoos which indicate the bearer has done an act of violence against a person of color.

“It’s one thing to confront someone [racist] in public where you just had absolutely no idea who they are. That’s one thing. But the folks who are closest to us — you know, that Klan stuff comes from the homes of people. Like, I’ve had people walk through the exhibit and said, ‘Oh, that’s my grandfather,’” El-Hakim said later.

El-Hakim’s museum eliminates the distance between curator, artifact and viewer, the curators said later. It makes it personal. A lot of people feel threatened by that. At CGCC, President Lawson stood in the audience; but if they brought the same museum to Florida or the Texas border, people would probably lose their jobs, El-Hakim said. “This has implications that are far reaching. Your president might be all good with what’s going on today, but when the threat of losing federal funds becomes attached to this, it becomes problematic, all right?”

What’s El-Hakim going to do with the museum, someday? This year, he’s starting a nonprofit called Black Seed Legacy Foundation, which will start community archives with pieces of his material. The communities receiving the items will commit to maintain and grow their new archive, maintaining public access.

“I see why some people don’t want to go back down that road, but it’s necessary,” he said later. “We have to have these conversations so we can get past some of this stuff, right? You have to learn how to be kind and loving and humane in society, especially at this time.”

•••

Students or alumni interested in joining EQUAL can email EQUAL@cgcc.edu.

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.