Riverkeeper hosts webinar

What are microplastics, and what are their effects on the Columbia River?

That was the subject of a webinar hosted by Columbia Riverkeeper on Dec. 15 featuring Kirsten Kapp, research scientist and professor of biological sciences and math at Central Wyoming College.

Lorri Epstein, water quality director, Columbia Riverkeeper, introduced Kapp, whose research focuses on microplastic pollution in freshwater ecosystems, and includes a study on microplastic hotspots on the Columbia and Snake rivers. She also co-authored a study identifying laundry dryer vents as significant sources of plastic microfiber pollution.

“Her work is so important for the Columbia River,” Epstein said. “Much of the research that’s happened on plastics has been on the marine environment, and while research on freshwater ecosystems has been increasing, it’s still limited. Its really cool to have such smart science and important research happening right here on the Columbia River.”

Microfiber shed from dryers

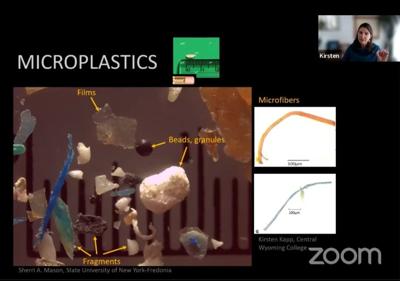

“Microplastics” are small plastic particles classified as smaller than 5 millimeters in size — smaller than a grain of rice or the tip of a pencil, she said. They come in a variety of shapes and sizes: Films, fragments, beads or granules and microfibers.

Microfibers are the most common type of found plastic worldwide, Kapp said. There are many types of fabric and, depending on makeup and weave, some shed more fibers than others in the wash. One study found there are 700,000 pieces of microfiber shed per garment per wash, though it can vary, depending on water temperature, detergent and type of washing machine.

But clothes dryers as a source of microplastic have not been studied until as recently as last year.

Kapp and colleague Rachel Miller ran an experiment, where they dried hot pink, 100% polyester blankets in two different parts of the country — Idaho and Vermont — using two different dryers. They used snow as a medium to collect the fibers emitted via the vent.

They chose a hot pink blanket because the fibers would be easy to differentiate from others in the fresh snow, measuring microfibers present at 5, 10 and 15 feet, as well as in a 30-foot arc around the vents. They found microfibers in every snow sample they took. In some cases, there were too many fibers to accurately count.

Most of the fibers turned up at the closest distance to the vent as expected, but, she said, “We also noticed that, when we had a persistent wind direction and wind speed, that altered the pattern of where those fibers were ending up, suggesting these fibers can act as a sail with the wind and travel much further distances.”

Because they didn’t test past 30 feet, they don’t know how far the fibers were able to travel. “But we do know, and can show based on this data, that dryers need to be brought to the table as washing machines have. We need to start looking at dryer design as a source of microfiber pollution … to reduce the amount of the microfibers being released into the environment.”

Effect on local water systems

At least 220 different species— including fish, birds, turtles, chickens, and mayflies — have been found to ingest microplastics. There are also ecosystem impacts, such as a mollusk that attaches itself to the microplastics, and then use the river and fragment to transport itself downstream to colonize a new environment.

“That’s a pretty significant risk that needs to be explored,” Kapp said. “Especially when you start talking about bacteria, and bacteria that colonize these microplastics in the environment.” There’s also a question of how these plastics alter the soil. “And when you start to alter your soil, you start to alter your ecosystem-level services,” she said.

The study of microplastics in the Columbia and Snake rivers began in 2016. At the time, there were only a handful of studies that looked at freshwater systems.

Beginning in Yellowstone, the researchers took water samples every 50 river miles; there were seven sample sites on the Columbia, some of which Kapp described as remote. Two samples were taken at each location: In a 2-liter mason-type jar, and a plankton net (mesh size 100 microns). They found plastics in 75% of the jar samples and 92.8% of the net samples; all of the net samples contained microplastics, as did six of the seven jar samples.

“We found films, we found fragments, we found beads, and of course we found fibers,” she said.

On the Columbia, hotspots included areas with very little human population, such as Brownlee Reservoir (though downriver from cities and agricultural zones), to areas with heavy recreational use, such as Cascade Locks.

Microplastics are ubiquitous in the environment, and the Columbia is no exception, she said.

“Plastic is not going away — it’s far too valuable a product,” she said. “And so there are ways that we can curb our use, reduce our use, of when we don’t necessarily need plastic.” For example, using plastics in hospitals is important — but not to eat dinner.

“You can rethink your choices,” she said.

To watch the webinar, visit Columbia Riverkeeper’s Facebook page, facebook.com/ColumbiaRiverkeeper/videos/3050618788539132.

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.