The way things work in the tiny town of Antelope, everybody just takes their turn being mayor.

Shortly after Margaret Hill’s turn came in 1981, so did the Rajneeshees.

The newly installed mayor of the town of 50 souls would soon face a terrorizing experience, becoming the focus not only of endless lawsuits from the followers of the Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, but of direct physical intimidation.

Through it all, Hill, who died at age 95 on April 22, served as a beacon of steadiness and strength for the besieged town.

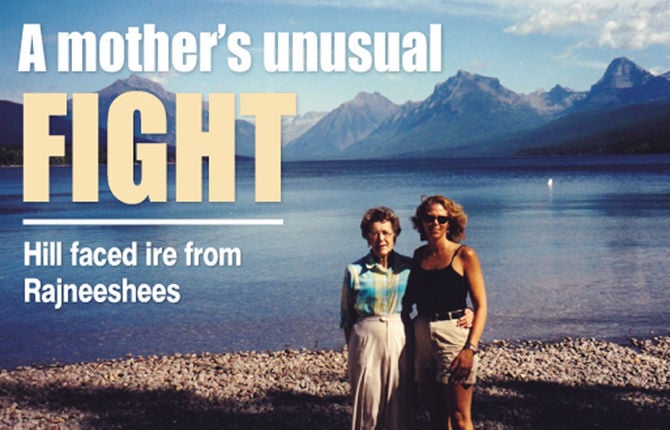

It is a bittersweet Mother’s Day for her three children and two grandchildren, as they prepare to lay her to rest on Monday.

Her daughter, Mollie Boyce, said, “I was just thinking about the things I enjoy doing, and they all come from her. She played the piano and sang, so we always sang. She loved to garden so we had a great big garden and beautiful flowers. We always baked bread.”

“We were very, very close. I loved her dearly, I called her every day,” said Boyce, who lives near Seattle.

During the Rajneesh years, her mom was so busy.

“It just consumed them,” Boyce said.

Hill was smart, well-informed and well-read, Boyce said.

“On one hand, it was kind of lucky for the people in Antelope” to have her mom as mayor. But on the other hand, it was “not lucky for her.”

Antelope resident John Silvertooth wrote a tribute to Hill on the Anderson’s Tribute Center memorial page, saying that Hill, frequently the spokesman for the community, had “a gallant image, composure and intellect and showed bravery in the face of danger. Her home was often the front lines and was the scene of the infamous arrest by the Rajneesh police force of freelance journalist Bill Driver, then reporting for Oregon Magazine.”

Hill, a longtime teacher, had just settled into retirement when she was tapped for the mayor post.

A few months later, the Bhagwan and his followers purchased the Big Muddy Ranch, 18 miles from Antelope.

“I remember her saying, if they’d just wanted their commune on the ranch and just stayed there, there probably wouldn’t have been much of an issue, but they wanted the town” of antelope, Boyce said.

“There were things they couldn’t do legally unless they were an incorporated city,” she said. “There was a lot of zoning things they wanted to do but couldn’t unless they passed a law, and they couldn’t pass a law unless they had a city.”

And so nearby Antelope fell into their sights. Town officials tried to snatch away the prize by pursuing a vote of unincorporation, but Rajneeshees, who had by then moved to town in some number, had enough votes to turn the measure down.

Eventually, there were enough of them to wrest away control of the city council and school board. They even renamed the city Rajneesh for a short time.

Hill told her daughter that the Rajneesh years were easily the most stressful of her life. Hill and her husband, Phil, soon began spending winters down south, expressly to get away from the situation.

Keith Mobley was the city’s attorney for the early years of the Rajneesh era. He said Rajneeshees had “developed a security force and they’d keep an eye on things and I guess [Hill’s] house deserved particular attention.”

She regularly had her house spotlighted at night as the Rajneeshees would drive by, her daughter recounted.

But they didn’t stop with that, of course, since they also arrested the journalist who was visiting them.

In those years, Boyce saw a side of her mother she’d never seen before.

The Rajneeshees had a team of about 20 lawyers targeting Antelope officials and others. “The thing I remember so much her talking about was the depositions [for lawsuits] and how excruciating those were,” Royce said. “They had a way of being — especially [de facto commune leader Ma Anad] Sheela — they were just nasty people. They were just mean, they would say things; they would insinuate things, none of which was true, just to cause problems.”

She said her mom “hated when she had to have anything to do” with Sheela.

Through this, Boyce saw in her mother “a strength and fortitude that came out. A side of her that was forced into existence that I hadn’t seen before. My mom was a great mom, she was always, always there for me, always. A wonderful grandmother. I have two sons and they loved her to pieces. But there was a business side to her.”

Boyce said her mom felt frustrated that the illegal activities in tiny, out of the way Antelope didn’t seem to draw much attention.

Her mother felt it was only when the Rajneeshees poisoned hundreds of people in The Dalles in 1984 that people really started taking notice.

In her working life, Hill taught in one-room schoolhouses and on Indian reservations and then finally in Kent and Antelope. She made such an impression that four or five of her former students came to her 90th birthday party.

Everybody always wanted Hill to write a book about her experiences, but “she said it was just too painful. Every time she kind of thought about writing a book and going through all that again she just couldn’t. It was really an awful time,” Boyce said.

Ellen McNamee was postmaster in Antelope for 30 years, retiring 18 months ago. She recounted Hill as a steadying force, who was doing what everybody else in town had to do, too.

“You cope because you have to, one day at a time,” McNamee said. “To keep people’s sanity they’d say, ‘Oh, they won’t last five years.’ And actually, they didn’t last quite five years.”

The commune collapsed in 1985 as key leaders were arrested or fled the country.

In the early days, as the world learned of the Rajneeshee’s presence in Oregon, Hill began getting letters from all over the globe, warning her about the nature of the new arrivals.

One letter in particular touched her as a mother.

A woman in South Africa wrote to Hill about how her son had gone to India to join the Rajneesh commune there. When the commune fell under the Indian government’s increasing scrutiny, the Rajneesh and his leadership simply fled in 1981, leaving behind their penniless followers who had given everything they owned to the Bhagwan.

The South African woman recounted how her son had to make his way home with nothing but the clothes on his back.

Mobley recounted how Hill maintained her cool throughout the ordeal. “She was very gracious, very pleasant. I never recalled having seen her lose her composure during all of that.”

It is the pleasant memories that her daughter is focusing on. She was a staff favorite at her assisted living facility in Hood River, with a wide circle of friends and always impeccably put together.

“She was one of the nicest people I know,” Boyce said. Her steadfastness for the people of Antelope didn’t just extend to facing down the Rajneesh, but of also seeing to the more simple needs of its citizens.

“I remember she used to bake an extra pie every once in awhile,” Royce recounted, “and take it over to this old man who lived in a one room shack in Antelope.”

Commented

Sorry, there are no recent results for popular commented articles.